What’s happening at the Line? Engineers analyse construction in Saudi Arabia from space

This post was originally published on this site

Civil engineers have shared their thoughts about the construction and engineering underway at Saudi Arabia’s linear city the Line by analysing satellite imagery of the expansive work site.

The Neom gigaproject in northwestern Saudi Arabia, and its flagship megaproject the Line, continue to attract controversy and questions about its feasibility.

In addition to state-sponsored brutality of indigenous people to make way for the project, the Line has proven controversial due to questions about its feasibility, necessity, cost and the drain it could have on global resources.

It also attracts public interest because of the lack of information coming from official sources.

A 170km long and 200m wide linear development in the desert, The Line is planned to be a “cognitive city” built in Tabuk Province. Bordered by two 500m-high walls, mirrored on the exterior, it is planned to be home to 9M residents in its 34km2 area and will be filled with interconnected mixed-use community spaces in its 135 modules.

Saudi authorities say it will run as completely carbon net zero and have no roads or cars, but public electrified transport running along the outskirts.

Little official information about the project

Very few updates are shared by the managers of the project, compared to the scale of the planned works. It is funded primarily or entirely by Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, the Public Investment Fund (PIF) and managed by various professionals.

An aerial image of Saudi Arabia and its neighbours with Tabuk City highlighted Source: Google Maps

Saudi Arabia does not allow independent journalism in the country, so it is not possible, for instance, for NCE to turn up at the location of the Line to verify what is happening without permission from the authorities.

NCE has contacted Neom press representatives for comment on numerous occasions but never received a response.

A closer in aerial image of Saudi Arabia with Tabuk City highlighted Source: Google Maps

Aside from commercial releases and updates from Neom executives on LinkedIn, open-source information is the primary method for trying to understand what is happening on the ground.

NCE used Google Earth and expert analysis to uncover some of what appears to be happening at the Line.

The images below show the visible footprint of the Line, with a red line applied by NCE to highlight where construction activities appear to be taking place.

An aerial image of the length of the Line highlighted in red Source: Google Earth

An aerial image of the west end of the Line Source: Google Earth

An aerial image of the east end of the Line Source: Google Earth

NCE spoke with Imperial College London Faculty of Engineering visiting professor in Mike Cook and Heriot Watt University School of Energy, Geoscience, Infrastructure and Society associate professor Rod Macdonald to analyse aerial imagery. Both Cook and Macdonald are former Buro Happold chairmen and senior partners.

Buro Happold has offices in Riyadh and continues to work on a variety of projects in Saudi Arabia.

Referring to the relatively small volume of news and updates from the Line’s managers, Cook said: “You can get random bits of information.

“I think it’s such a crackpot idea, as surely everyone agrees who is involved in city planning, to have something of such a scale, to think that you’re going to build it within a few years is unrealistic.”

A shorter, broken, wobbly Line?

The scant updates create a huge space for speculation to run rampant, with rumours earlier in 2024 saying that the 170km city was going to be shrunk to 2.4km. This was eventually denied by Neom leadership.

Even AtkinsRéalis, a delivery partner on the Line, quotes it as measuring 140km, 30km less than the official measure.

Cook said he could understand the perception that lengths shorter than 170km are being quoted, given that looking along the line from the Gulf of Aqaba in the west, it “crashes into some mountains” in the east.

In addition to visible challenges like mountains, Macdonald said: “If you build something 170km long, you’ve got to think about thermal expansion and concrete shrinkage, and in that area, you have to think about seismic [activity].”

Speaking further about seismic activity, he said: “It’s not very major, bit there is some seismic activity around those mountains on the Western side of Saudi Arabia” which sit on the eastern end of the Line.

Macdonald said inserting gaps in the mirrored walls along the outside of the Line would be a way to mitigate the impact of thermal expansion and seismic activity. “If you’re talking about [a] 170km long [structure], and you have some breaks along the way which are 20cm wide, you’re not going to see that [given the scale of the structure relative to the gaps],” he said.

An aerial image of the Line showing an interruption to its depth Source: Google Earth

If you look along the Line on Google Earth, it is not a uniform trench. There are many peaks and troughs. Macdonald commented that “you wouldn’t want to have 170km that you [drive around] to take your construction vehicles from one side to the other”, so the interruptions to the depth of the Line are likely to be roadways to allow for the transit of vehicles.

An aerial image of the Line showing an interruption to its depth Source: Google Earth

Moving mountains

Most of the footprint of the Line on its western side is on open, relatively flat ground, but in the east it hits the northern tip of the Hijaz Mountains.

There is lots of evidence on Google Earth showing machinery moving materials in the mountainous area. It is difficult to infer what methods of groundworks are being used, but Macdonald said “they might be blasting, [but] you have to get special licenses to use explosives in Saudi Arabia”.

“Generally speaking, they use breakers and they just break and break and break and break,” he added.

An aerial image of the Line in a mountainous part of Saudi Arabia with large vehicles visible Source: Google Earth

Macdonald said limestone is prevalent in Saudi Arabia and it is often broken up without explosives to make way for development.

“Perhaps it’s a bit easier in the limestone, but if they can get away with not using explosives, they will do it, even to the extent that they have hundreds of guys and diggers and big vibrators and big breakers and just break it up,” he said.

An aerial image of the Line in a mountainous part of Saudi Arabia with large vehicles visible Source: Google Earth

Macdonald explained that it’s difficult to get explosives in Saudi Arabia because of concerns around them getting into the wrong hands.

Supply chain constraints

NCE asked what physical, non-financial constraints there would be for the managers of the Line.

“Where do you start?” Cook said. “Materials availability at this scale; there’s a finite, steady supply of steel and concrete in the world that isn’t particularly able to suddenly double its output.”

For the Line to be completed by its supposed target of 2030, Cook it would need to be constructed at 15,000 times the rate of normal UK construction times.

However, Macdonald, who has worked on projects in Saudi Arabia, said: “I think you should never underestimate the Saudis with regard to the rate at which they can build something.”

Cook echoed Macdonald’s comment about ambitious build rates, and said: “There’s a strong incentive to create something that can be seen from space. I would have thought there was a desire to scrape a line across the Earth as quickly as possible.

“And I would think there’s going to be strong pressure on designers and contractors to start work and to come up with a work plan that allows them to start work before they have resolved all the questions they would ideally have resolved.”

He also said it “does suggest it’s going to have a big global impact” on construction material supply chains. He said he had spoken with Neom representatives who said there was a “strong recognition of the massive supply problem” regarding the vast volumes of materials needed for construction.

“To get enough concrete there, they have to bring it in from all around the world,” he said, but noted that there is one cement plant “reasonably close” to the Line.

“It’s way behind the program that we were led to expect at the very beginning,” Cook said. “Getting concrete from a port, because it has been shipped in, 170km to the other end of the Line [would slow construction].

“There’s obviously lots of very clever people working away at it, and they’re coming up with logical sequences of construction.

“It’s important that the professionals are listened to, and not scared into having to say what people want to hear.”

Evidence of progress

Activities along the Line appear to be very varied. In some areas the only evidence of construction are dirt roads marking out the edges of the linear city, while there are huge trenches visible in others.

Cook said there appeared to be “focus perhaps on the middle third” of the project.

Cook said “strength of vision must be an important thing” for the managers of mega projects like the Line.

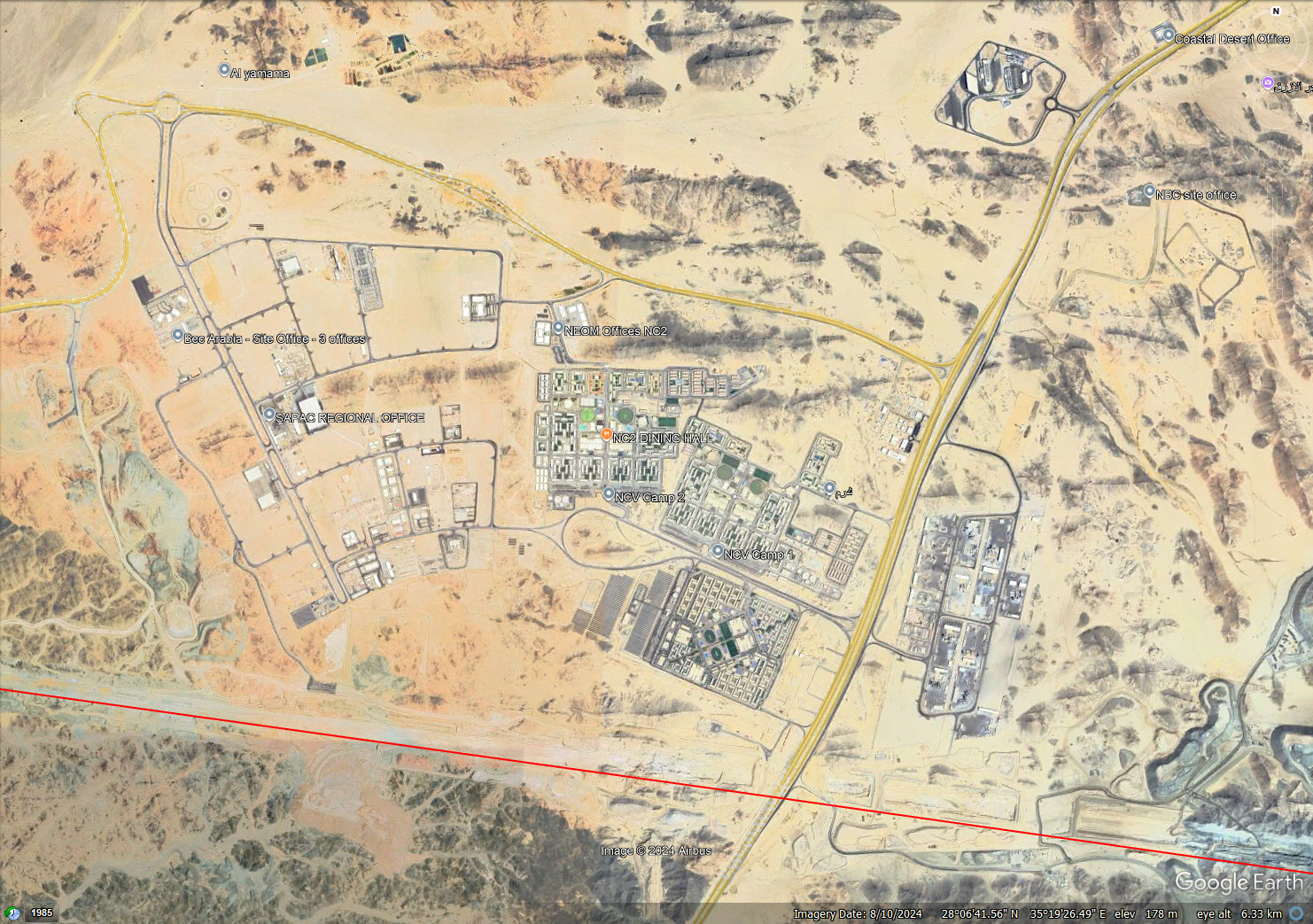

“Sometimes visions are not ready to be executed,” Cook commented, but noted the presence of “some townships with sports facilities” and places of worship indicate that the “precursor to there being some level of focused development” exists at the Line.

Settlements near the Line

Macdonald said he thought the majority of the settlements being built next to the Line are intended for people building it.

An aerial image of the Line with a significant settlement next to it Source: Google Earth“They can’t go and live in Tabuk and commute out there every day; they have to live on site,” Macdonald said, referring to people working on the site, including manual labourers and professional services workers.

An aerial image a Line settlement with sports facilities visible Source: Google Earth

“I have seen signs of what looked like piles areas for these communities on either side of the Line, rather than on the Line,” he continued. “The building [work] inevitably has to focus on building sufficiently to bring people to build.”

An aerial image a Line settlement with possible evidence of piles visible Source: Google Earth

NCE pointed out areas around existing settlements next to the Line which are clearly marked out for expansion. Some are even labelled as areas for expansion on Google Earth.

“That suggests that they are setting themselves up properly in order to do a major bit of fast construction,” Macdonald said.

“You will need to have massive construction accommodation for the number of people that are going to be working on the site, so I’m not surprised that they’re building it up.

“You need a certain number of people to be around manning some massive great big diggers and earth moving equipment, but you need 10 times as much in terms of labour in order to do the later works in the building project.”

An aerial image of the Line with a significant settlement next to it Source: Google Earth

He said he thought he could “see a lot of competence” based on the clear intention to expand accommodation and “they put in a sensible amount of roadways”.

Commenting on the long-term future of the settlements, Macdonald said: “They might be building into [the settlements] some of the services that are required for the Line. They might be building sewage works and things like that.

“But if the project is successful, I can imagine they wouldn’t want something like that nearby, they would want to get rid of it.”

Water at the surface

Water is visible at the surface at various parts of the Line, but the sources and purposes of it are not clear.

An aerial image of surface water visible at the Line Source: Google Earth

“All around the world, we know rainstorms are becoming more major,” Macdonald said. “As you raise the temperature of the oceans by one degree, the amount of evaporation goes up dramatically and it’s got to come down somewhere.

“Traditionally, around Saudi Arabia when you get rain, it’s heavy.

“You need to have aggregate, sand, cement and water to build. You can’t afford to run out of it. If you run out of one of those, you can’t build, so they would have to store water.”

An aerial image of surface water visible at the Line Source: Google Earth

Macdonald said that elsewhere in Saudi Arabia, water is pumped from 100m below ground “on a continual basis” and there’s “enormous desalination of water” from the sea to enable sustainable drinking water supplies.

“The whole city of Riyadh is [using] either water pumped from a deep aquifer or pumped up from the Gulf,” he explained.

“It may be that what they do [at the Line] is set up desalination plants with pipelines and they use them initially for construction and later on for the occupation.”

An aerial image of surface water visible at the Line Source: Google Earth

Flat versus irregular base

Analysing the construction of the city itself, Cook said: “It doesn’t look like it has got further than ground preparation, which starts off with getting everything to the necessary level.”

As to whether there is any benefit to having an entirely flat base for the Line, rather than having the ground level at different heights across its length, Cook said it may depend on whether the managers believe a straight line includes the ground itself being straight.

“Is man going to control nature and charge through at a level?” he commented.

“You could imagine that, even if that was the vision at the outset, practicality might creep in and people might say, ‘well, it wouldn’t be so difficult if we step up several stories’.” This would mean not having to remove our plough through the mountains in the east.

“You’re still talking 150 stories, so if you step up 30 stories and reset your level when the Line goes over the mountains, it could save billions,” Cook added.

Climate impact

Cook said his “passion” is “to try and persuade as many people as possible to take the climate emergency very seriously” and said he had worked with the Institution of Structural Engineers and the Institution of Civil Engineers on climate action.

“When I see the level of construction [at the Line] with this extraordinary level of carbon footprint to execute it, forget about energy consumption. In the next 10 years of construction, the impact on the climate will be massive,” he said.

Reflecting on how the construction of Neom could be done more sustainably, he said: “Using more local material, rather than having to import cement and concrete would be good.”

An aerial image of the east end of the Line showing a possible tunnel entrance Source: Google Earth

Macdonald said Neom had a “big aim to disturb the surrounding countryside as little as possible” and said “they may be mining to get the materials they want” as a way to minimise impact.

An aerial image showing a possible tunnel entrance just beyond the east end of the Line Source: Google Earth

Like what you’ve read? To receive New Civil Engineer’s daily and weekly newsletters click here.

Responses