Robots in construction are far from science fiction

This post was originally published on this site

There’s a way to go yet before construction robotics becomes a familiar fact of life, but the technology is certainly making ground. Tim Clark reports

If you are heading to UK Construction Week in Birmingham next month, there is a good chance that within the halls of the National Exhibition Centre you’ll come across a robot or two.

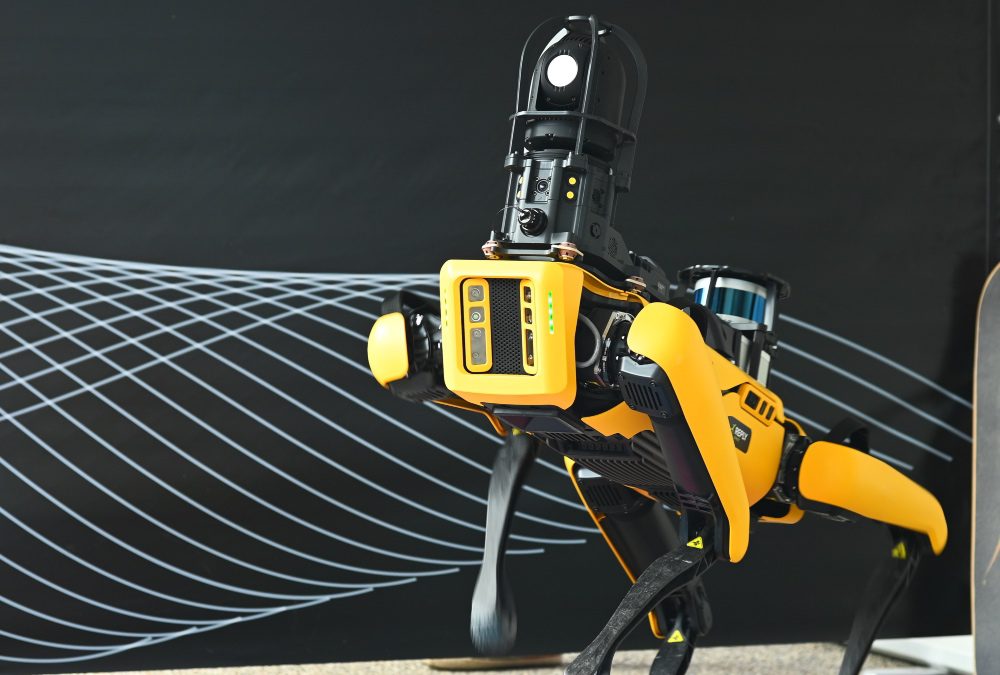

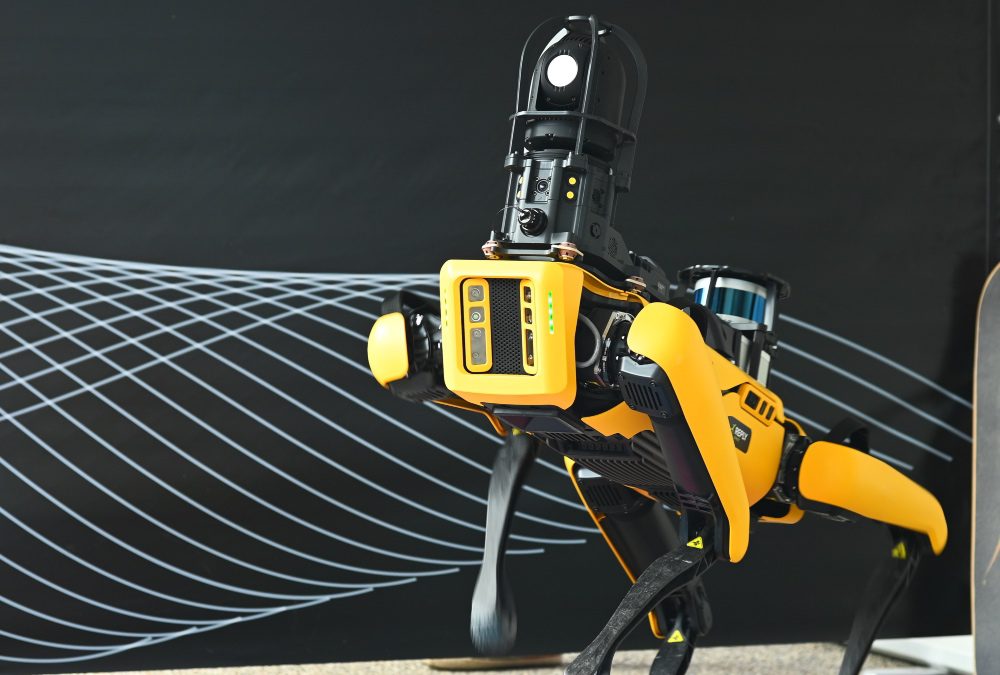

From Boston Systems’ robotic dogs to Hewlett Packard’s self-driving SitePrint machine, which outlines site layouts, robotics promises to make its mark on the construction industry.

Like many innovations, the main aim is to help find a replacement for dwindling workers within the sector, and raise productivity across the board.

The question for many is how far has robotics come, and what evidence is there that it is changing the industry?

Build in Digital recently looked at the progress of drones in the construction sector. One area where drones, robotics and AI is expected to dovetail is the way that site machinery may in the future be monitored and moved autonomously from above.

Robotics may however really take off when it is integrated with BIM.

As explained in Build in Digital’s recent micro-conference on robotics, a number of factors are driving the adoption of robotics and automation in the sector. The increased demand globally, not just in the UK, for housing and infrastructure has arguably put pressure on the industry to deliver projects faster and more efficiently.

As the Royal Institution for Chartered Surveyors’ (RICS) head of AI, Andrew Knight explained, pressures within the industry from new building regs to meeting net-zero targets are also acting as drivers of innovation.

Technological advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and sensor technology are also playing a crucial role. Additionally, the push for sustainability is encouraging the use of robots to reduce waste and energy consumption on construction sites.

Age of cooperation

Another initiative that is being pondered is cooperative robot fabrication (CRF), which means that tasks can be completed that couldn’t be done if robots were acting alone. This type of cooperation could have a huge impact on how the construction sector operates.

To make use of CRF, it is best to imagine construction moving away from the site and onto the factory floor. Any single robot has a limited type and number of actions it is able to complete.

However, by coordinating different sets of robots, multiple functions can be completed. This idea comes into its own when it comes to constructing modular homes.

The CRF method has been tried multiple times in manufacturing, from furniture to cars. Housing or large-scale modular construction is a natural next step,

A recent publication: A circular built environment for the digital age, edited by Catherine De Wolf, assistant professor of circular engineering for architecture at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology of Zurich; Sultan Çetin PhD student at the Delft University of Technology, and Nancy M. P. Bocken, professor in sustainable business at Maastricht University, outlines the processes needed to digitise a number of areas of the economy, including robotics in construction

The authors state that CRF at the building scale is common for the in situ construction of large structures, or for performing work that requires complex task sequencing beyond what is possible by a single robot working alone.

They state: “CRF is typically used within laboratory environments. However, if research expands from static industrial robots towards mobile machines and large-scale construction machines, the technology could be directly applied on construction sites to enable more material-efficient construction and engender faster and more precise disassembly and reassembly processes.

“This wealth of data can be used to design more materially efficient structures, better evaluate overall structural performance during fabrication, and measure parameters like the stiffness or degree of damage to a member.”

Robots may even be able to help in the design of more resilient buildings of the future by using sensors to undertake “non-destructive” testing of structures and collecting data on the outcomes.

In November, Swiss firm ABB Robotics announced a partnership with car manufacturer Porsche to begin work on a modular housing design. Speaking at the time Eberhard Weiblen, chairman of the executive board at Porsche Consulting, said: “The construction industry is facing numerous challenges. Highly automated factories for buildings can deliver higher quality and more affordable housing.

“In combining ABB’s leading robotic solutions and Porsche Consulting’s knowledge in planning and running state-of-the-art factories, we want to help transform this important industry.”

How such a partnership will work out remains to be seen, but car manufacturers have the know-how to recreate the precise production lines that modular house-builders crave. Rather than emulating the car industry, partnering with it could be a sensible option.

Laying the foundations

The industry was first given a taste of what could happen with robotics when SAM – which stands of semi-autonomous mason – was launched almost a decade ago by US firm Construction Robotics.

The robot can cost around $500,000 and lay between 2,000-3,000 bricks per day, which is a number of times more than arguably any professional bricklayers can manage.

The technology has arguably been around since the 1960s when the first Motor Mason was produced in the UK, and numerous types of robots were produced in Japan in the 1970s and ‘80s.

However the original forerunners of today’s robots never truly entered the construction marketplace. With its new robot Construction Robotics promised that SAM could achieve 10x productivity gains. Although impressive, the semi-autonomous nature of SAM meant that there was still a large amount of human input into the final product.

In 2022 construction firm Ballast Nedam launched its own robot that promised to use up to half the mortar of a traditional human bricklayer, a mere 455 grams per brick, compared to circa 1kg for a human.

According to Ballast Nedam the robot is able to measure the facade so it knows “how to level the masonry, even if the lifting scaffold wobbles”. Feedback on how the robot performs is fed to developers to allow the machine to learn.

According to Bas Meerwijk of Dutch construction firm Heddes Bouw & Ontwikkeling, which is a subsidiary of Ballast Nedam, the robot is learning from the mistakes: “When something goes differently than expected, I discuss it with the ROPAX developers. I then send the log files [points for improvement, ed.] and the software is adjusted. The next day, the robot has had an update and has improved a little further.”

As Mollie Claypool, co-founder and chief executive of Automated Architecture (AUAR) noted on Build in Digital‘s recent micro conference on robotics and automation: “Essentially, we are applying robotics to very old problems.”

AUAR licences its own low-cost (which it describes as low CapEx) micro-factories to add to existing housebuilders’ suite of tools available to build new homes. Combined with a proprietary operating system, the startup can strip back the thousands of production lines usually involved in the building process to just a couple.

The company has partnerships in the US and Europe and plans to roll out its “lego houses” having raised £2.6m in funding. Robotics firm ABB is one of the main investors in the business, however at present the firm has one micro-factory operational in Gent, Belgium.

As the sector begins to explore how robots can be used for more purposes, the technology to help make operations more autonomous will also advance. From robots tying steel rebar to tightening curtain wall fixings, the applications that have been mechanised will grow and become more adept at handling the intricacies of construction sites, not only the factory floor.

It may be that a complicated answer to a simple question is what has been needed in construction for a while.

Firm’s changing the robotic construction landscape

Odico Formwork Robotics

Danish firm Odico launched its own robotics offer in 2018. The robot was designed to fit inside a shipping container to make it easier to transport to individual construction sites. Once unloaded the robot can construct concrete formwork.

AUAR

With an ambition of simplifying the supply chain and cutting down the estimated 7,000 parts in a typical home, robotics-construction start-up AUAR aims to meet architects and contractors in the middle.

With an up-front fee of £250,000 to install, and then monthly fees for service, the company will provide robotics and software to streamline the construction and price of new homes.

The ultimate aim is to provide low-cost affordable housing, using less materials and automated production.

nLink

If the factory-made homes are going to move off the production line then robotics such as nLink’s highly accurate positioning, motion control and application control robots will be key.

The Norwegian firm’s aim is to replace dirty, dangerous or dull work with machines, which can also optimise material flows. Projects include mobile drilling robots, and robotic boom lifts. A drilling and bracket mounting robot was designed to change tools and fasten brackets for curtain walls.

Komatsu

Aiming to ‘build machines to answer the needs of society’ Komatsu was first formed in 1921 and today the company is a global giant when it comes to construction and mining equipment.

When it comes to robotics the firm aims to develop smart construction equipment and autonomous mining trucks. The company has even invented underwater electric bulldozers and has prototyped an excavator that can work on the moon.

Image credit: Antonello Marangi/Shutterstock

Read next: Threading the information gap in building safety

Are you a building professional? Sign up for a FREE MEMBERSHIP to upload news stories, post job vacancies, and connect with colleagues on our secure social feed.

Responses